This final post, from a series of eight, draws from an archive of recently discovered audio recordings of America's most important modern poets, taken during Pearl London's renowned poetry seminars at the New School. The most compelling moments of these conversations were transcribed and published in Poetry in Person: Twenty-five Years of Conversation with America's Poets (Knopf), named by CSM "One of the ten best (nonfiction) books of 2010." The book is just now out in paperback.

The announcement of Philip Levine as our new (American) Poet Laureate is bold and just. Levine deserves recognition for his affecting, imaginative, and occasionally brutal verse rooted solidly in the experience of the working class. In a time of economic hardship and political polarity, Levine's selection couldn't be more relevant. Plus, a shine on the apple, at 83, he's a mensch. Levine continues to write and teach poetry at the highest level.

Interestingly, the announcement increases to an even half dozen the number of Poets Laureate featured in Poetry in Person.

All the poets visited London's class before they were named laureates--in some cases, well before. Philip Levine, for instance, was a guest in her seminar more than thirty years earlier. Below are some excerpts and audio clips of interviews with each, in chronological order of their laureateships:

Maxine Kumin, Poet Laureate, 1981-1982

Maxine Kumin visited Pearl London's class in 1973. That same year, she won the Pulitzer prize for her fourth book, Up Country: Poems of New England. During the seminar, Kumin explains the role of poet:

"Because, you see, this is what I conceive the function of the poet to be. Not to moralize, not to polemicize, not to grieve, not to praise, and not to damn. But to name, to tell, to authenticate, to be specific, to support what he sees and what he feels. I suppose if I have a credo, that would be the credo that I have."

Robert Hass, Poet Laureate, 1995-1997

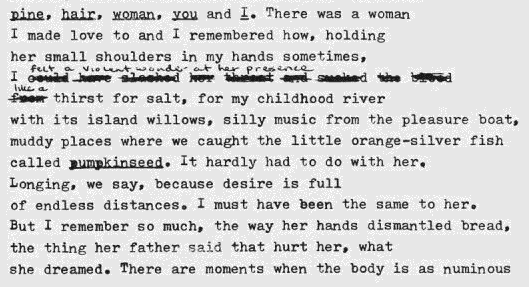

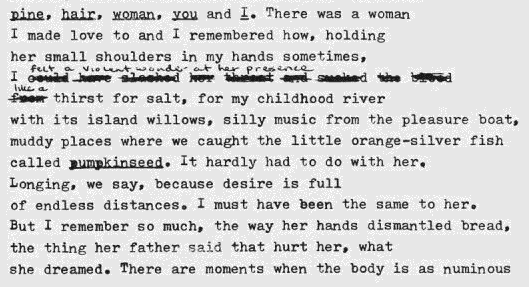

When Robert Hass visited Pearl London's class in 1977, he brought with him a typed and notated draft of his poem, "Meditation at Lagunitas." The poem went on to become one of Hass's most celebrated poems. Speaking with London, he confessed that the poem made him nervous; in the poem, he said, he wanted to "use abstract language and talk directly about ideas and use a long line and deal with what I was feeling and still have a poem."

Robert Pinsky, Poet Laureate, 1997-2000

Robert Pinsky was a guest in London's seminar in 1993. A tireless champion of poetry as a spoken art, Pinsky tells this story during his visit to Pearl London's class about a group of young professionals who took to heart his admonition to always read poetry aloud:

[audio:https://alexanderneubauer.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/pinsky_readingaloud.mp3|titles=pinsky_readingaloud]

Louise Glück, Poet Laureate, 2003-2004

When Glück was the guest poet in Pearl London's class in February of 1979, she read one of the poems she was working on for her not-yet-released Descending Figure. It's called "Autumnal":

[audio:https://alexanderneubauer.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/Gluck-reading-Autumnal-2.mp3|titles=Gluck reading Autumnal 2]

Public sorrow, the acquired

gold of the leaf, the falling off,

the prefigured burning of the yield:

which is accomplished. At the lake's edge,

the metal pails are full vats of fire.

So waste is elevated

into beauty. And the scattered dead

unite in one consuming vision of order.

In the end, everything is bare.

Above the cold, receptive earth

the trees bend. Beyond,

the lake shines, placid, giving back

the established blue of heaven.

The word

is bear: you give and give, you empty yourself

into a child. And you survive

the automatic loss. Against inhuman landscape,

the tree remains a figure for grief; its form

is forced accommodation. At the grave,

it is the woman, isn't it, who bends,

the spear useless beside her.

As I discussed in a blog post last year, this poem achieves an "egolessness" that nonetheless remains coupled with an intensely personal experience—a competing pair of qualities that Gluck told London was one of the aims of her poetry.

Charles Simic, Poet Laureate, 2007-2008

Charles Simic was a visitor during one of the last few years of London's classes, which stretched to more than twenty-five years by the time she retired in 1998. While he was there in April of 1995, he shared his working draft for "Official Inquiry Among the Grain of Sand':

Philip Levin, Poet Laureate, 2011

And so we come to the newest American Laureate, Philip Levine. Levine visited Pearl London's class in 1978; he later wrote that, at the time of the visit, "I believe I was writing at my very best, although it would be the books the come that would win me the prizes." Below is the final typescript of his "You Can Have It":

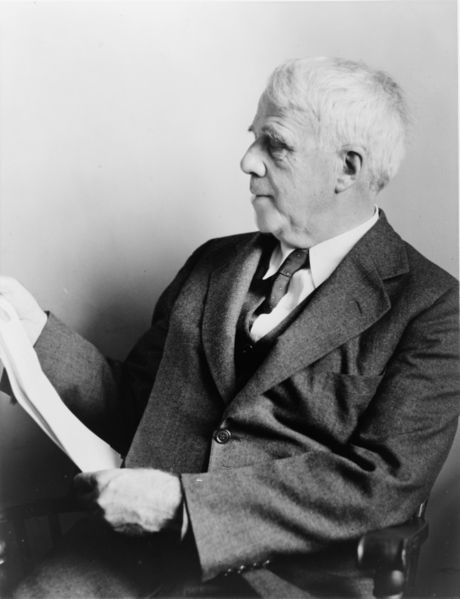

One thing I was surprised to find, as I started listening through the tapes of Pearl London’s classes, was how often the name Robert Frost came up in her conversations with poets. Frost has fallen out of favor with the academy in the decades since his death, relegated to Hallmark cards and middle school pick-your-favorite poem assignments. Here, however, he seems to have become a poet’s poet, celebrated for verse, prose and a very modern mood of darkness.

One thing I was surprised to find, as I started listening through the tapes of Pearl London’s classes, was how often the name Robert Frost came up in her conversations with poets. Frost has fallen out of favor with the academy in the decades since his death, relegated to Hallmark cards and middle school pick-your-favorite poem assignments. Here, however, he seems to have become a poet’s poet, celebrated for verse, prose and a very modern mood of darkness.