This seventh post, from a series of eight, draws from an archive of recently discovered audio recordings of America's most important modern poets, taken during Pearl London's renowned poetry seminars at the New School. The most compelling moments of these conversations were transcribed and published in Poetry in Person: Twenty-five Years of Conversation with America's Poets (Knopf), named by CSM "One of the ten best (nonfiction) books of 2010." The clips used below are all taken from the audiobook companion to Poetry in Person, offering extended, thirty to sixty minute cuts of eight of the best conversations.

"Poetry begins in loss, begins with alienation, and speaks against our vanishing." So Edward Hirsch tells Pearl London when he visits her poetry seminar in 1993. The poetic experience, as Hirsch tells it, is "an encounter with the worst," a kind of confrontation with negativity and darkness, in which one tries to find "something" to bring back out into the light. Here's how he puts it:

[audio:https://alexanderneubauer.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Edward-Hirsch-on-loss.mp3|titles=Edward Hirsch on loss]Hirsch calls Orpheus's decent into hell the "archetypal poetic experience," as he attempts to recover his dead wife by going into the underworld after her. Ultimately, however, Orpheus's story ends not with triumph over loss but with the doubling of it; having convinced Hades to allow him to bring Eurydice back to the upper world, he violates their agreement by looking back at his wife before they have completed the journey out of hell. If the poetic experience truly is modeled on Orpheus's journey, then although the poet may "try to bring something to the light," he will never entirely succeed; he will think he has triumphed over loss, only to have it slip, devastatingly, away.

The metaphors that other poets use to discuss loss are likewise colored with a sense of almost certain failure. Seamus Heaney once described Elizabeth Bishop's poetry as one that "ingests loss and transmutes it," and Eamon Grennan notes that Heaney's poetry does the same thing. But Grennan says that he doesn't think of his own writing in quite those terms—his poetry is the narrative account of the "act of wrestling" with loss. This is how he explains it to London:

[audio:https://alexanderneubauer.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Eamon-Grennan-on-loss.mp3|titles=Eamon Grennan on loss]Quite bluntly, Grennan says that his poems often record his inability to absorb, to "transmute" loss. And William Matthews says his poems are grounded in a loss that one tries to obscure with a "ground cover, or even a magnificent topiary garden"—but, as Matthew's says at the very end of this clip, "I can always see it through the leaves:"

[audio:https://alexanderneubauer.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/William-Matthews-on-loss.mp3|titles=William Matthews on loss]

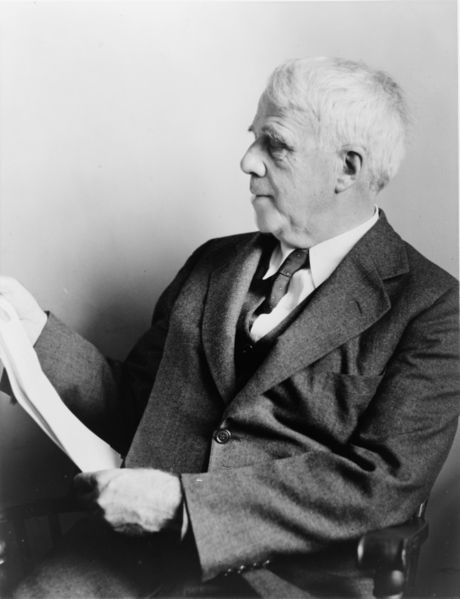

One thing I was surprised to find, as I started listening through the tapes of Pearl London’s classes, was how often the name Robert Frost came up in her conversations with poets. Frost has fallen out of favor with the academy in the decades since his death, relegated to Hallmark cards and middle school pick-your-favorite poem assignments. Here, however, he seems to have become a poet’s poet, celebrated for verse, prose and a very modern mood of darkness.

One thing I was surprised to find, as I started listening through the tapes of Pearl London’s classes, was how often the name Robert Frost came up in her conversations with poets. Frost has fallen out of favor with the academy in the decades since his death, relegated to Hallmark cards and middle school pick-your-favorite poem assignments. Here, however, he seems to have become a poet’s poet, celebrated for verse, prose and a very modern mood of darkness.